I was fascinated by Canada as a teenager. It came from

looking at pictures in books that I borrowed from the local lending library and,

while I appreciated the skyscapes of the prairies, it was the grandeur of the

mountains, the lakes and the forests that had the most appeal. There was also

the sense of scale and the vastness of it all.

The interest in the Canadian landscape re-surfaced when I was

an undergraduate. Fascinated by animals and plants, I knew that I wanted to continue

to study Biology by conducting research in the field. I mentioned this, together

with my feelings about the boreal landscape, to one of my lecturers and he kindly

put me in touch with possible research supervisors in Canada. These contacts resulted

in several provisional offers, providing I could get funding from teaching assistantships or research

grants. However, nothing more came of it and I stayed in the UK; my fascination

for boreal landscapes being given reality when I studied lakes and rivers in northern

Sweden and in Finland. It was in these countries that I could get a sense of

wilderness; of something that appeared to show no influence of humans. I can

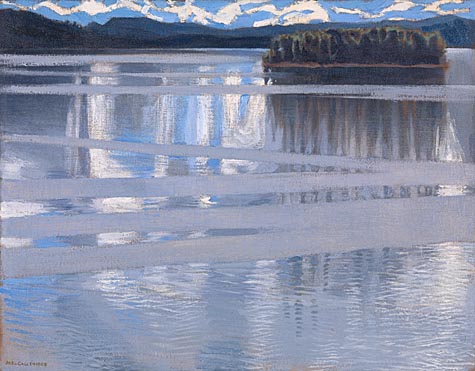

sum up this sense by using, as illustration, Gallen-Kallelas’s painting Lake Keitele (see below). Gallen-Kallela

was a seeker of “virgin Nature” and I can easily empathise with that [1].

During my undergraduate years, I spent many happy Saturdays visiting

the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery (as it was then) in London. Torbay,

where I grew up, was not a centre for looking at a wide range of paintings and

I felt drawn to the galleries and to certain works. It wasn’t because of any

skill that I had in art, as I have no artistic talent, but I felt a strong connection

with some of the images and the way that landscapes had been portrayed. It was

similar to looking at pictures of Canada when I was younger - something “clicked”

and I didn’t know why, nor was I interested in thinking about that.

As an old man, I realise that my interest in the boreal

landscape, and the various ways in which it was illustrated in great paintings,

were part of the same identity – I am an unabashed Romantic with a love of the

sublime. The latter possibly comes from a religious upbringing that clearly

influenced me, even though I left formal religion when I was twelve. It now

takes a nebulous form, but it is certainly there (and not only in paintings,

but also from music and poetry). While artists like Caspar David Friedrich and Harald

Sohlberg introduced Christian symbolism into their paintings of sublime

landscapes, there seems to me something even more powerful if the landscape

overwhelms without any obvious theistic force (although theists might suggest

that I was just being blind).

It’s not to say that I don’t appreciate both natural and

painted landscapes that do show human influence. The Renforsen rapids on

the River Vindel in northern Sweden always fill me with awe [2] and, during the

spring flood caused by snow melt in the mountains, there is something about

their impressive power that certainly stirs the soul. There are, however, so

many signs of human influence here: bridges, paths, a hotel, a café, mill

buildings, car parks, etc. that one realises it is far from wilderness. If part

of the splendour of being in wilderness comes from tranquillity, Renforsen,

other rapids, and raging seas are part of another kind of awe; that which

contains an implied threat. Compare Gallen-Kallela’s Lake Keitele with Johan Christian Dahl’s The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss (see below) to see examples of

this contrast. Both portray the sublime.

Of course, the art and aesthetics of the sublime have been

written about many times and I’m not saying anything new. Rather, in a

pretentious way, I’m trying to understand my personal view of landscape and

what has made me so enraptured by some natural and painted scenes. I’m hooked.