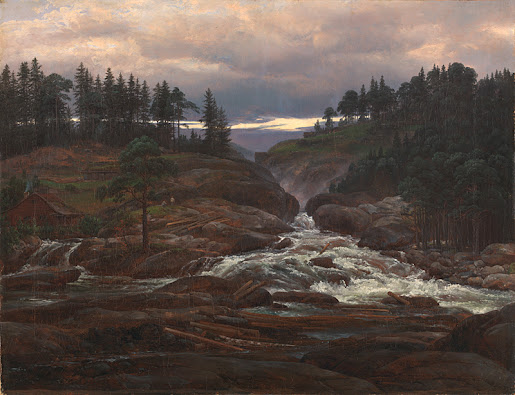

Johan Christian Dahl’s The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss (1827) provides a striking image of the power of water. It is a painting of the sublime and there is much to see within the work [for a large-scale image click on the link in 1]. The waterfall (foss in Norwegian) charges towards us from between large rocks before the river bends away to our right and the mist that we see in the middle distance provides evidence of even greater turbulence upstream. We just make out a mountain in the far distance, so we know the landscape setting, but Dahl’s low-level view focusses our attention on the middle distance and foreground.

We note that many tree trunks are scattered around, having become snagged after they were heaved into the river to be carried to sawmills downstream, a practice that was common in Scandinavia before trucking. To the left, we see logging activity and two men are seen on rocks just to the left of the river and these loggers, together with the occupied wooden cottage, give scale to the picture. There are more cottages in the distance, one precariously close to the chasm through which the river flows, while the other has a meadow on which cattle are seen. The combination of dramatic landscape and rural activities is typical of Dahl, who followed the tradition established by the 17th century painters Jacob van Ruisdael and Allaert van Everdingen [2].

Johan Christian Dahl was brought up in Bergen, and the surrounding mountainous landscape, with its cascading rivers, formed an impression that stayed with him for the rest of his life. After being apprenticed to a painter in Bergen, he continued his studies in Copenhagen, where he saw Nordic landscapes by Dutch masters [3]. He began to be recognised for the paintings he exhibited there, and his success allowed him to become a professional artist.

Dahl had an elevated view of landscape painting, his chosen genre, and, as Marie Bang states [2]:

…he claims that “landscape painting can have the same effect on the heart as history painting, when the painter presents the objects in an interesting way.” Here we see Dahl under the influence of academic coercion and the hierarchy of genres, where history painting with its moral message stood at the top of the ladder and landscape painting at the bottom; topographical prospectus painting being hardly regarded as art at all, but as a purely mechanical copying of nature without the artist’s creative influence.

Dahl’s Romantic, emotional view of landscape permeates all his work and he was fortunate in having Prince Christian Frederik (later to become King Christian VIII of Denmark) as a patron and supporter. On travelling to Dresden in September 1818, Dahl gained further support from Caspar David Friedrich who was [2]:

..fourteen years older and an established artist, but the two found in each other a common love of nature and a sincere depiction of nature based on self-study more than on the well-established academic clichés that they both deeply hated.The enclosed, melancholy Friedrich expressed his transcendental longing in distinctive mood landscapes, while the outgoing, lively Dahl tended towards more down-to-earth and dramatic motifs. Despite their close friendship and their deep love for nature, the two had no profound influence on each other; they were too different in temperament and artistic goals.

As was mentioned earlier, Dahl retained a passion for Norway and its dramatic topography describing himself as [2]:

..a “more Nordic painter” with a “preference for sea shores, mountain nature, waterfalls, sailing ships and harbour pictures in daylight and moon light”

He made a long-awaited trip back to his homeland in 1826, visiting the Labro falls, among other places - the inspiration for the 1827 painting. Sketches were made and these formed the basis of works to be completed in his studio [3]. In the Introduction to Forests, Rocks, Torrents, Christopher Riopelle [3] writes:

A painting like The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss of 1827, executed for an English client, results directly from Dahl’s long study of the Norwegian landscape at its most tumultuous. At the same time, it is the product of slow and painstaking studio work....For Dahl, the aesthetic merit of the painting lay not in the motif but in the artist’s ability to ennoble it. It was this higher, more complete vision – the eternal Norway of the mind’s eye, fruit of long reflection – at which Dahl always aimed....it did not matter where Dahl was when he chose to paint Norway. The snowy peaks, the cascading torrents, the impenetrable forest of the true north did not need to be in his line of sight; rather, memories of Norway, contemplated in the tranquillity of the studio, could be prompted by oil sketches made on the spot..

I, too, love Nordic landscapes but by adoption, having been fortunate to make many visits to Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway. In the summer of 1975, I joined researchers from the University of Lund on a project on a tributary of the Vindel River in Swedish Lapland and I returned in 1976, not only to continue the project, but because I was captivated by the landscape and the beauty of the river. After a spell working on the biology of a lake outlet in Finland, I returned to the Vindel river and a project with my late, and much missed, colleague Björn Malmqvist from the University of Umeå. Renforsen on the Vindel was especially important to me, and, during ice-melt in the mountains, the rapids are indeed sublime. You will gain an impression of the majesty of Renforsen from the video clips cited below [4,5], where you will note the barriers to prevent the build-up of logs at the margins, for the river was used, like the river in Dahl’s painting, for the transport of tree trunks to mills downstream.

The Vindel River is unregulated, but many other rivers have been dammed to provide a head of water to drive hydro-electric schemes. This fate also befell the Labro falls, as can be seen in an aerial view from Google Earth (see below, together with an image taken by Per Vestøl of the power station located close to the point shown in the painting). The natural falls are still in existence (see the Google Earth image), but their flow is controlled – quite different to the Labrofoss of the early Nineteenth Century.

I wonder what Dahl would have thought of the change? As a passionate supporter of Norwegian identity, maybe he would be proud to see that natural resources were being harnessed. But the sense of the sublime has been diminished. Instead of the power of Nature over humans, so evident in Dahl’s painting, we now have the opposite. Most of the magic has gone.

[1] https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/johan-christian-dahl-the-lower-falls-of-the-labrofoss

[2] Marie Lødrup Bang (2020) Johan Christian Dahl. Store Norske Leksikon [in Norwegian] https://nbl.snl.no/Johan_Christian_Dahl

[3] Christopher Riopelle (2011) Forests, Rocks, Torrents: Norwegian and Swiss Landscape Paintings from the Lunde Collection. London, National Gallery Company.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=os6fCk2CTWk&ab_channel=johnjairo41

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qK4-5YOKcg

No comments:

Post a Comment