When growing up in Torbay, I was fascinated by all the creatures

that lived in rock pools. In addition to fish – blennies, gobies, butterfish,

pipefish – there were many invertebrates. Limpets and barnacles could not easily

be removed, as their defence against being swept away by waves, and attack by

predators, also deterred human collectors. However, a wide variety of crabs, snails,

worms, sea anemones, and many other creatures were collectable and I took some to

observe in an aquarium tank. This was the early 1960s and I don’t know whether

I would have spent hours on the shore had I been a young teenager today, with a

mobile ‘phone, computer games, etc.. I like to think that I would, as I have

never grown out of a child-like enthusiasm for “rock-pooling” and am only prevented

from this pleasure today by living 100 miles from the sea.

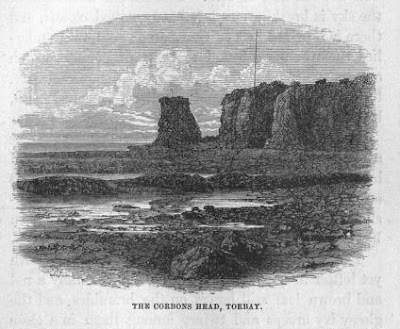

One of the richest collecting spots (see above) was the

rocky coast just to the north of a promontory called Corbyn’s Head (or Corbyn

Head). At low tide, there are wide stretches of flattish sandstone rock, with

many pools that contain easily-lifted boulders and large stones. Perfect for those

interested in the creatures of the shore, but I was so fixated on the hunt that

I never asked myself where the boulders came from, although I knew that they must

be the result of erosion somewhere. I now know that they were likely to come from the promontory

and that Corbyn’s Head has changed considerably over the last 200 years. Going

much further back, we know that sea level rise after the Ice Age swamped a

forest that filled much of what is now Torbay [1] and the rise in water level, together

with storms, then eroded the Head.

As recently as 100 years ago, there was a stack off the

headland and this was first formed into an arch before the whole collapsed. In

the first photographs above, we see the appearance of the stack in 1928 and

this can be compared to the contemporary appearance of the headland (above,

lower). In an earlier engraving, taken from Gosse’s Land and Sea [2], we

see a tall stack that is almost the height of the rest of the promontory and without the hole of the arch. Of

course, there may be some artistic licence here, but this image (see below), from the mid-1850s,

shows how Corbyn’s Head (referred to by its old name of Corbons Head) must have

looked 150 years ago.

Anyone brought up in South Devon will feel an affinity for

the red soils of the area and these derive from sandstones that were, in turn,

formed by the compression of ancient sands and muds. It is a soft rock and is

easily eroded, as I knew well as a child. Our house was faced with sandstone blocks

and one of my household jobs was to sweep up the red dust that accumulated on

the tiles of our verandah. On a much larger scale, there were also cliff falls;

the most recent of which [3] was caused by sandstone rock becoming saturated and

then collapsing under its own weight, as cracks widened and the whole became unstable.

Sandstone may also contain pebbles washed by some ancient dramatic

flood and this composite is called breccia. At Corbyn’s Head we have layers of sandstone

overlain by breccia and a full description is given in the excellent, well-illustrated

review of the local geology by West and Csorvasi [4].

I wonder what the coast

of South Devon will look like in a few hundred years’ time, when global warming

will bring further increases in sea level and when climate change may bring

more violent storms? Will generations to come look at images from their holiday

at the coast and remember fondly walking by cliffs and headlands that are then

very different in appearance?

[2] Philip Henry Gosse (1865) Land and Sea. London, James Nisbet & Co.