I lived in Oakenshaw for over two years, arriving in Spring 1971. It was a mining village in County Durham and consisted largely of a long row of terraced cottages, but I knew little of its history when I arrived.

The move to Oakenshaw came at a difficult time for me. I had started my PhD at the University of Durham in 1970, working on the ecology of blackfly larvae in Upper Teesdale streams and my supervisor, Dr Lewis Davies, was someone I looked up to for his expertise. I’d spent the previous two years on blackfly research at the University of Salford and it had been a miserable experience, as my supervisor was not an aquatic biologist (he was a medical parasitologist) and I lived alone in bed-sitting rooms. Fortunately, I had very supportive friends among the research students and technicians, and I needed them. In December 1968, a policeman rang the bell to my room (that leaked rain around the bay window and had a mouse infestation) to tell me that my father had died; this rather cold way of contacting me, being the only method of conveying such news quickly. I was, of course, upset (my mother having died in 1960) and I headed out into the Cheshire countryside to stay with my brother’s in-laws, who were very kind to me during my Manchester days.

My supervisor showed kindness in understanding what I was going through and, after a short break of a week, I was back at my bench and carrying on with counting and identifying larvae from Artle Beck. Fortunately, my girlfriend from undergraduate days was still part of my life and, in the summer of 1969, we went together to Cyprus by rail and sea, stopping off at interesting places en route. She had just finished a teaching course at the University of Southampton and was taking up a post at a school in Cyprus and it was good for us to have some time together, although that was much more from my side than hers. Little did I know that my departure from Nicosia airport would be the last time I saw her, and I received a "goodbye letter" some days later. It’s all a bit of a sob story, isn’t it?

Early in 1970, I saw an advert for the studentship at Durham and I went for interview, having previously visited Dr Davies to get confirmation of some of my identifications. I loved Durham and its magnificent buildings the first time I saw them and was thrilled to get the position, even though I had not passed my driving test and had to do so. That was motivation enough, and a successful test was completed in the weeks before I left Salford. Arriving in Durham, I was given laboratory space and was relieved to find that my fellow research students were as nice a group as the ones that I’d just left. Friendships were made quickly and I went with Dr Davies to select streams for the study. I had the use of a Land Rover (identical with the one below) and soon immersed myself in sampling, walking alone over the fells with a rucksack of jars, bottles and other bits and pieces, sometimes in foul weather.

I was told to rear some adult blackflies from pupae that I had collected and then pin them into an insect box (something that I had never done before) and I learned some new sampling techniques that I was somewhat dubious about. Anyway, I cracked on and then made a trip out to some new streams, accompanied by Dr Davies, who at one point said “Roger, you seem to be completely incompetent”, probably because of my fly-rearing and pinning, not the most interesting part of the study for me. We had an uncomfortable ride back to Durham and, as I was unloading the Land Rover, Dr Davies came out to tell me that my girlfriend of the time had died on the Isle of May, where she was studying seagulls. She was 24 years old and, although she had had some mental health issues, it was completely unexpected.

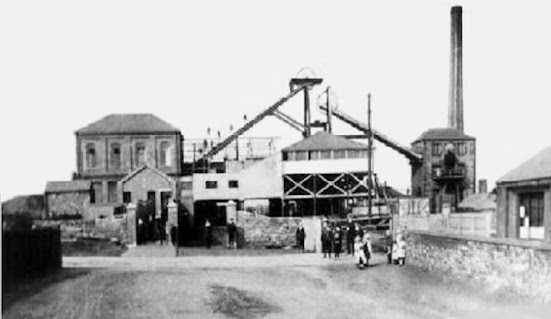

So, after that long pre-amble we come to Oakenshaw, where a very good friend, and fellow research student, had bought a miner’s cottage (see above for “The Row” [image by Peter Robinson]), modernising it with an inside bathroom and with storage heaters to keep the place warm. I was very happy living there, although it was a distance from Durham and the bus service was infrequent (three a day in each direction, if I remember correctly). When I was going out on field work to Cronkley Fell, or to Moor House [1], I could use the Land Rover and park it overnight outside the cottage, but there had to be a better solution. That’s how I came to own my first car, a 2-door Morris Minor - 913 HBM – that had 94,000 miles on the clock and had been a rep’s transport. I had a lot of faith in that car, despite its consuming oil as well as petrol, although I was not pleased when a front wheel went awry and nearly fell off (“the usual kingpin problem” according to the garage).

They were happy days and, when Dr Davies returned from many weeks spent in the Crozet Islands on his own research, he recognised that I had done a lot of work while he was away and I had numerous sheets of results to prove it. Good times, then, but I couldn’t ignore thoughts of the previous occupants of the cottage who must have been miners, as it was likely owned by the mine that was located at the end of the road (see above, the road from which the image was taken is the one leading to the cottages). There were still ex-miners living in “The Row” and the social club further down the road could still be very lively on Sundays. Oakenshaw Colliery had a narrow seam (the 3 ft Brockwell seam [2]), so work as a miner was extra tough and there were inevitable fatalities in accidents (summarised below), in addition to deaths from other causes.

Fatalities at Oakenshaw Colliery (data extracted from [2])

Age range

16-20 10

21-29 8

30-39 5

40-49 7

50-59 3

60+ 1

Cause of death

Fall of stone 28

Waggonway

accidents 4

Accidents with

machinery 6

Others

2

1850s 3

1860s 6

1870s 11

1880s 8

1890s 3

1900s 3

1910s 3

1920s 2

Later 1

So many lives lost and of young miners, too. It put my earlier miseries into perspective, and the cottage that was a happy home may well have experienced tragedy in earlier years. Certainly, the figures - and chatting with ex-miners - brought my life as a research student into focus and I can’t imagine what it was like to work in those narrow seams and have no alternative employment; something that became acute when the mine was closed. That left Oakenshaw as a Category D village (to receive no development [3]) in 1951 and the houses then sold off cheaply, allowed to run down, or even be demolished.

There was still accessible coal, however, and a large open-pit operation was commenced behind the row of cottages at the time I left, now returned to be farmland (at least it was at my last visit). As I reminisce, I realise that life in Oakenshaw was as valuable for my education as working on a PhD.

[1] https://rwotton.blogspot.com/2018/04/tempus-fugit.html

[2] http://www.dmm.org.uk/colliery/o002.htm

[3] https://redhillsdurham.org/the-story-of-category-d-villages-and-lyr/